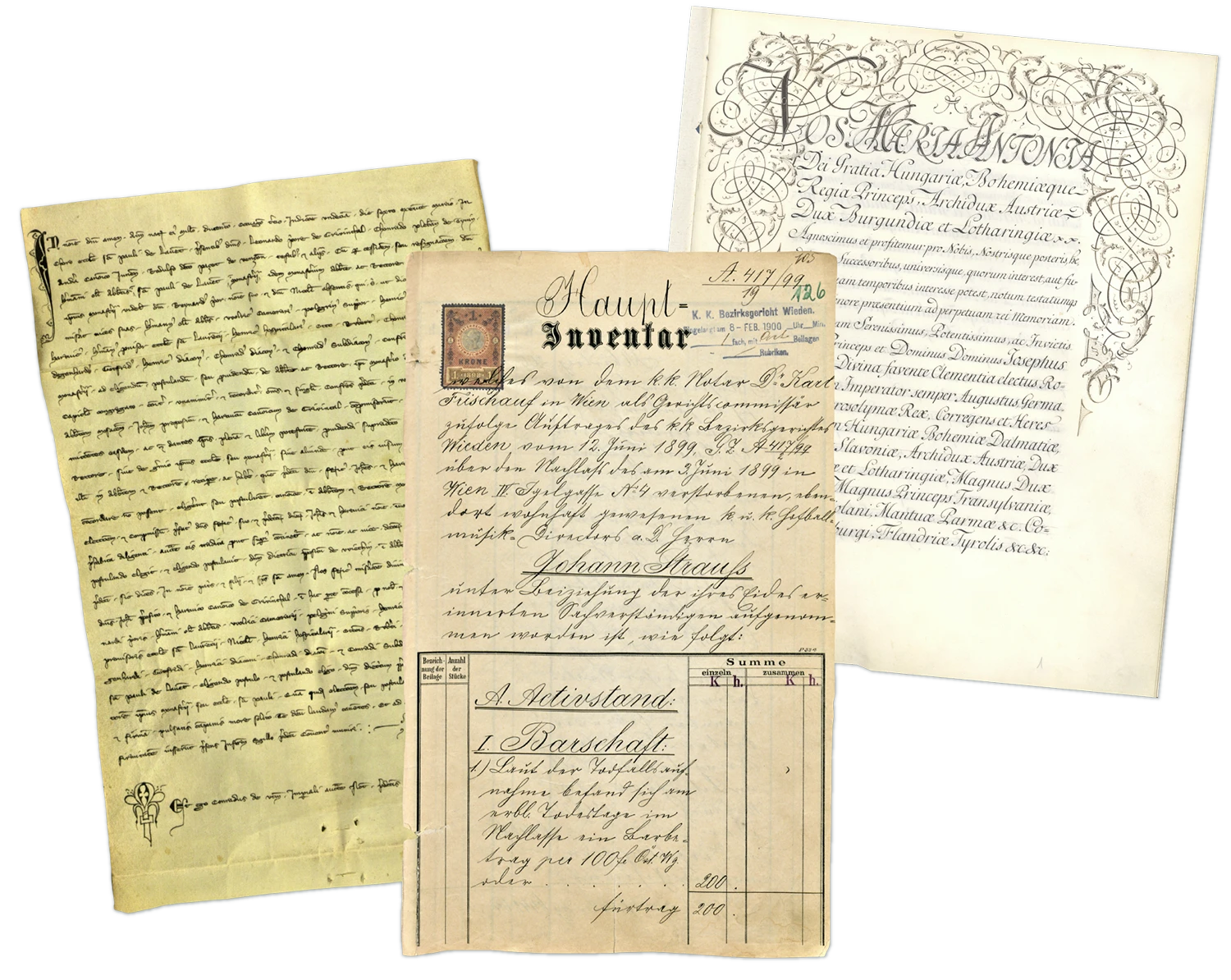

1283 - Notarial deed on the course and outcome of the election of Dietrich, Canon of the archbishop's domain of St. Peter’s in Salzburg and Provost of Wieting [district of Eberstein], as Abbot of St. Paul’s, held at the Benedictine monastery of St. Paul in Lavanttal in Carinthia, Austria

on 26 March 1283

In Latin monasticism, an abbot has served as the head of monastic communities since late antiquity. In the early Middle Ages, the Rule of St. Benedict endowed him with comprehensive leadership functions, to be exercised with regard to important matters in accord with his fellow monks. The choice of abbot is entrusted to the monastic community itself; in the Middle Ages, the relevant bishop, who was also responsible for consecrating the abbot- elect and conferring on him the regalia of office (cross, mitre, sceptre) as symbols of the authority vested in him, was entitled to approve the result of the election.

The position of abbot at the Benedictine Canons of St. Paul in Carinthia [district of Wolfsberg] had become vacant after the renunciation of the serving Abbot [Hermannus] on 27 February 1283. The new election was held in the church choir of St. Paul’s in the presence of several Carinthian clerics. Some of these witnesses are mentioned by name in this document, including the Prior of the Canon Abbey of Griffen [Grivinthal; district of Völkermarkt) as well as a Canon of the Abbey of Eberndorf [Juna, district of Völkermarkt]. The assembly of monks, including the abbot who had stepped down, authorised a panel of three electors to propose and elect the new abbot. These electors – the Benedictine Abbot of Moggio [Mosacense near Udine], the Griffen Provost and a Canon of Griffen – settled on Dietrich [Pruchler], Provost of Wieting [Wiechin near St. Veit / Glan].

Konrad von Udine [Conradus de Vtinis] was entrusted [rogatus] with notarising the election process. He presumably came to St. Paul’s in the company of the Abbot of Moggio in order to provide the monastery with a certification of the electoral process that was valid under canon law so that the Archbishop of Salzburg could then arrange for the consecration of the abbot-elect. As an (imperial) notary public [imperiali auctoritate notarius publicus], Konrad was authorized to draw up documents with full probative force, which he authenticated in handwriting with the attachment of his signet. The electors confirmed the accuracy of the facts established in the deed on their own behalf and on behalf of the Monastery by affixing the seal of St Paul’s.

Written in Latin, the document was drawn up by Konrad according to the rules of the ars notaria valid at that time and inscribed on parchment. The text consists of a single block; only a few punctuation marks provide the reader with some orientation. The numerous abbreviations common at that time make comprehension difficult. The deed does not contain all the elements later stipulated for notarial instruments by the Imperial Notarial Ordinance of 1512. The present document can be attributed to the category of notarial deeds accompanied by an extraneous seal, presumably not placed next to the notary’s signet but – dorsally – on the reverse side.

This seal is missing on the original, which is kept at the Austrian State Archives, Department Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Allgemeine Urkundenreihe, bearing the number 1829. A complete edition of the document (including the abbreviations in full) can be found in: Urkundenbuch des Benediktiner-Stiftes St. Paul in Kärnten, published by Beda Scholl, Vienna 1876, 171-173 (No 132).

1770 - Document of Renunciation, signed by the Archduchess Maria Antonia (later known as Marie Antoinette), daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor Francis I of Lorraine and of the Habsburg monarch Maria Theresa, on 17 April 1770 in Vienna on the occasion of her marriage to Louis, the Bourbon heir to the French throne

Renunciation is generally defined as a legally binding waiver – in the present case it relates specifically to a waiver of claims of inheritance and succession. In 1700, the War of the Spanish Succession broke out after the senior Spanish line of the Habsburg family had come to an end. In 1703, the Habsburgs responded to this situation by forging a mutual pact of succession – initially kept secret – for the Habsburg dominions in their entirety. After their defeat in the war against the French Bourbons in 1713, Emperor Charles VI, then head of the family, ordered the pact to be promulgated. The succession to the throne was based on the principle of male-preference primogeniture. In the absence of a male descendant in all family lines, the eldest daughter of the last holder of the throne was to be pronounced heir (and, subsequently, her descendants, with preference given to male descendants): such a situation arose in 1740 after the death of Charles VI and resulted in the succession of Maria Theresa as ruler of the Habsburg dominions. The two daughters of Joseph I, the elder brother of Charles VI, who had died in 1711, had to renounce any inheritance and succession rights upon entering into marriage (which they did with crown princes of Saxony and Bavaria in 1719 and 1722, respectively).

Following the marriage between Maria Theresa and Emperor Francis Stephen of Lorraine (1736), the House of Habsburg no longer suffered from a lack of male descendants. Maria Theresa shifted the focus of Habsburg foreign policy and sought to forge an alliance with the former enemy France by establishing marriage ties with the Bourbons: her eldest son, Joseph II, married a Princess of Parma in 1760 – the marriage did not bring any descendants; his younger brother Leopold II, on the other hand, durably connected Tuscany with the House of Habsburg-Lothringen through his marriage in 1765 (he had twelve sons); two sisters, Maria Carolina and Maria Amalia, married princes of Parma and Naples-Sicily, respectively. Maria Theresa aimed at establishing ties not only with these Bourbon sidelines, but also with the royal house of France. Already in 1766, she had selected her youngest daughter, Maria Antonia, to help achieve that objective. The initial plan to betroth the then eleven-year-old princess to the 56-year-old Louis XV was abandoned in favour of a marriage to his grandson, the Dauphin Louis: in 1769, the latter’s grandfather thus came to Vienna and asked the Habsburg princess for her hand in marriage on behalf of his heir to the French throne. After she had reached marriageable age, the two families came to an agreement with regard to the matrimonial property regime for the 15-year-old groom and his by then 14-year-old bride on Easter Saturday of the following year, 14 April 1770. After the Easter holiday, on 18 April, Maria Antonia’s renunciation of any claims to succession was formally enacted. The marriage was officiated the next day at Vienna’s Augustinian Church; absent from the ceremony, the Dauphin was represented by proxy by his brother-in-law of the same age, the Archduke Ferdinand Karl Anton, the bride’s youngest brother – whilst a festive wedding ceremony with her husband the Dauphin followed in Versailles on 16 May after Marie Antoinette’s arrival in France.

The Deed of Renunciation was signed by Maria Antonia in the atrio majori of the Hofburg Palace in Vienna – in the presence of the imperial couple (“coram … Majestatibus”) and the French ambassador Aimeric Joseph de Durfort-Civrac, as well as nearly 100 further witnesses (“praesentes et testes”) from the Court administration led by State Chancellor Kaunitz. Heinrich Gabriel Collenbach, a diplomat in the service of the State Chancellery, authenticated the document in his capacity of “ad hunc actum Autoritate Caesarea creatus Notarius publicus”. This was the same formula as had been used already in 1713 for authenticating the promulgation of the Pragmatic Sanction, for the declarations of acceptance issued from 1720 onwards by the estates of all dominions, as well as for the declarations of renunciation made by the daughters of Joseph I in 1719 and 1722.

The Latin document is inscribed on parchment, bearing the signature of the special ad hoc notary as well as his seal imprinted on lacquer in lieu of a signet, because Collenbach, in his capacity as ad hoc notary, had no such signet. The seal of the princess and the signature “Antonia” in her own hand are attached to the document with a cord affixed with lacquer followed by the list of witnesses. The document thus follows the format of a document with seal authenticated by a notary. The original is held in the Austrian State Archives, at the Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv. It is part of the Habsburg family document holdings and bears the number 2055 (in the archive’s directory it is erroneously dated 18 April 1770).

1900 - Probate inventory of the estate of Johann Strauss

Probate inventory of the estate of Johann Strauss, drawn up on 22 January 1900 by the notary Dr. Karl Frischauf, at his legal office in Wieden, Vienna’s 4th district.

Johann Baptist Strauss (Johann Strauss the Younger) was born on 25 October 1825 in St. Ulrich, a suburb of Vienna, at Rofranogasse 7-8 (today 1070 Vienna, Lerchenfelder Strasse 15), as the son of Johann Strauss (the Elder) and Anna Strauss. Although he grew up with music due to his father’s profession and showed great talent, his father wanted him to work at a bank. From 1836 he attended the Schottengymnasium in Vienna’s 1st district and subsequently the commercial branch of the Polytechnisches Institut in Vienna as of 1841.

It was only following the death of the composer Joseph Lanner in April 1843 that he opted to pursue a career as a musician and left the Polytechnisches Institut to obtain a solid music education from renowned Viennese teachers. He set up his own orchestra and made his successful debut on 15 October 1844 in Vienna’s 13th district, Hietzing, at Dommayer’s Casino (at the site of today’s Parkhotel Schönbrunn).

In the early years of his career while still largely unknown to the general public, the inexperienced composer and instrumentalist received support from several friends and benefactors in Vienna’s music scene. Adopting the pattern of his father’s Musikwerkstatt (and in competition with the Elder Strauss) they collaborated as a team in writing and orchestrating music. In order to avoid this rivalry with his father, he undertook several tours to the crown lands of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, but also to Belgrade and Bucharest. After his father’s unexpected death on 25 September 1849, Johann Strauss combined his own orchestra with his father’s and went on concert tours to Berlin, Racibórz, Wrocław and Warsaw.

Through the good offices of the Warsaw music publisher Rudolf Friedlein, Johann Strauss received an invitation from Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, who was staying in Warsaw at the time. The performances before the Russian Tsar and Tsarina and the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, who was also in Warsaw, marked a big breakthrough. In 1852 he celebrated his first great musical success with the Annen-Polka. Between 1856 and 1865 and again in 1869, Johann Strauss spent several summer months in Pavlovsk near St. Petersburg. His greatly acclaimed performances there saw him ultimately emerge from his father’s shadow.

In 1863, he was finally awarded the coveted title of k.k. Hofballmusikdirektor after his previous requests had been denied in 1856 and 1859 due to his activities during the revolutionary year 1848. Among the numerous tours made by the composer – by then an international celebrity – particularly noteworthy appearances included Paris on the occasion of the 1867 World Exhibition, London, Boston and New York in 1872, Italy in 1874, St. Petersburg and Moscow in 1886 and Berlin in 1889. Numerous awards which he received in the course of his lifetime are ample testimony to his international fame.His private life was not as successful as his musical career. His first wife was Jetty Treffz. She was seven years older and fulfilled the functions of lover, housekeeper, secretary and surrogate mother all at once. They were married on 27 August 1862 at St. Stephen’s Cathedra in Vienna, but Jetty died prematurely in 1878. A few weeks later he wedded a singer from Wrocław, Angelika Dittrich , called “Lili”, who left him four years later. In order to be able to marry his third wife Adele, who was 31 years younger than Strauss, he converted to the Protestant faith in 1887, left Austria and became a citizen of Saxony-Coburg, where Duke Ernst II enabled him to divorce his second wife and remarry.

It was on 22 May 1899 that he conducted his operetta Die Fledermaus for the last time at the Vienna Court Opera. Flushed with the effort he caught a cold and developed pneumonia, of which he died on 3 June 1899 in Vienna, at Igelgasse 4 (now Johann-Strauss-Gasse 4). He was survived by his third wife, Adele Strauss, but left no children. Provisions in his last will exclude his brothers and sisters from succession. The assets listed in this probate inventory, in particular securities, properties, orders and medals, awards and musical works, attest to his economic and social success as well as to his musical prowess.In drawing up the notarial document listing the estate of Johann Strauss, the notary Dr. Karl Frischauf, with his office in Wieden, today the 4th district of Vienna, acted as court commissioner. The Notarial Code of 1855 already provided for notaries performing the function of court commissioners. It was only in 1970 that the respective provisions were amended by the Court Commissioners Act (Gerichtskommissärsgesetz) of 11 November 1970, which stipulated that notaries of the court district having jurisdiction for the deceased were to be designated at the court’s behest as court commissioners for probate proceedings.

The proceedings also include drawing up a probate inventory based on information provided by the heirs, through enquiries to banks, authorities and land registers, as well as appraisals by court experts. In the capacity of court commissioner, notaries are public servants within the meaning of the Criminal Code. They prepare all decisions and documents for judicial settlement, ensure that the lawful heirs become owners of the estate and thus contribute substantially to easing the work burden of the courts.As far as the notary Dr. Karl Frischauf is concerned, it can be noted that he was elected President of the Lower Austrian Chamber of Notaries on 9 December 1889, a function which he exercised until 1899. He retired as a notary in 1902 and died on 30 August 1911 at the age of 76. The probate inventory, drawn up and signed by the notary Dr. Karl Frischauf in his capacity as court commissioner, was also signed by three appraisers for securities, properties and valuables, respectively, by the notary Dr. Julius Richter, having his office in Vienna-Landstraße, now the 3rd district of Vienna, as executor and administrator of the estate and by Richter’s assistant Dr. Edmund Kundegraber, who represented the widow Adele Strauss and her daughter Alice Epstein. Dr. Julius Richter was appointed notary in 1892 for Vienna’s first district. Before this appointment he served as the first chairman of the Association of Lower Austrian Notarial Candidates, founded on 26 October 1888. He died on 17 August 1905 while still in office. Dr. Edmund Kundegraber, who was appointed notary in 1916 for Vienna’s first district, died in office in 1925.

Large parts of the present inventory were written in an old script called German cursive, which is no longer in use today and therefore difficult to read for the general public. The penultimate page of the inventory contains a summary of the estate’s assets written in Latin script. It shows that Strauss left a remarkable estate worth 834,494.67 kronen. It must be noted that, upon the request of the heirs, the inventory precisely recorded the royalty rights deriving from the great musical oeuvre of the deceased but left the financial appraisal for a subsequent record. In 1892, one krone corresponded in purchasing power to about 10.2 euros. In 1892, the gulden that had been used in Austria since 1858 was replaced by the krone at a ratio of 1:2, but remained in circulation until 1900. The present inventory is therefore drawn up using both currencies. Other notable aspects are the numerous medals and orders awarded to Johann Strauss by Austria, Prussia, Coburg-Gotha, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Russia, Turkey, Persia and the French Legion of Honour listed under item III Valuables (Pretiosen), as well as his extensive real estate property listed under item VII. The original of the document is kept in the Vienna Stadt- und Landesarchiv (WStLA) under HptA-Akten, Persönlichkeiten S29.3 (Vlft.Johann Strauss).