1670 - Annuity purchase by Jean-Baptiste Lully from Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, known as Molière

Paper, handwritten, 4 ff. 34 x 22,5 cm, Paris, National Archives, Central Register, ET/CXIII/72 (RS/402)

December 14, 1670Under the Ancien Régime, annuity purchase was the most traditional way to borrow money and have access to capital. Through this annuity purchase, Jean-Baptiste Lully, the settlor, borrowed money from Molière. The latter gave him a capital of 11,000 pounds; in return, Lully had to pay him 550 pounds per year. These are the annuity arrears and the interest on the capital held. Lully, as indicated in the margin of the first page of the document, reimbursed his loan to Armande Béjart, Molière’s widow, in May 1673, a few months after the Molière’s death in February 1673. Those who are sensitive to the great men of the century of Louis XIV will appreciate to see on the same document the signatures of both Jean-Baptistes, accompanied by that of Madeleine Lambert, Lully’s wife.

Source: Des minutes qui font l’histoire, Somogy Editions d’Art / Archives nationales, Chambre des notaires de Paris, 2012

1727 - Will of Boris, Prince Kurakin, Russian Minister of State, adviser to Peter the Great and ambassador to the King of France

Paper, handwritten, 4 ff, 33 x 22,4 cm, Paris, Archives Nationales, Central Register, ET/XXXIX/335 (RS/293)

5 August 1727Prince Kurakin’s first wish, when he received the two notaries at the Châtelet de Paris in the room of his hotel on rue de l’Université, “overlooking the courtyard and the garden”, was to be transported after his death to Moscow, to be buried in the Chudov monastery, located within the Kremlin.

It was his son, Alexander, who was naturally entrusted with the vast majority of the paternal inheritance. First, everything that maintained an aristocratic lifestyle worthy of its rank as an ambassador: furniture, of course, but also silverware, horses and carriages.

But most of his legacy lay in the capital he had invested with foreign banks: in Holland, Vienna, Saxony, all these places also recalling his career as a diplomat, which he also tried to pass on to his son.

The prince’s career is exceptional. He studied in Venice at a very young age, participated in the campaigns of Pierre Le Grand and obtained his first diplomatic mission at the age of 30 with the Holy See. His successes led him to abandon the career of arms for that of diplomacy and he had one mission after another with the support of the tsar of whom he was also the brother-in-law: first Hanover, then Holland and England, before his appointment as extraordinary and plenipotentiary ambassador in Paris in 1724.

His descendants also had to show a great sense of negotiation and among them his great-grandson Alexander Borisovich Kurakin is especially remembered, as ambassador to Vienna and Paris and an important negotiator in the drafting of the Tilsit Treaty in 1807.

Source: 122 Minutes d’histoire, Acte des notaires de Paris, XVIème-XXème siècles, Somogy Editions d’Art / Archives nationales, Chambre des notaires de Paris, 2012

1761 - Obligation by Joseph François Dupleix, former General Commander of the French Establishments in India, with respect to two Amsterdam merchants

Paper, handwritten, 33 x 22 cm, Paris, National Archives, Central Register, ET/XVI/745 (RS/50)

18 january 1761This act shows the two sides of Dupleix’s Indian adventure. The original copy of the authentic act thus describes, on seven pages, an impressive number of jewels and gems, symbols of his success and enrichment. It lists earrings, necklaces, bow ties, rings and tiaras estimated at a considerable 451,684 pounds, including a pair of candle holders worth 45,400 pounds, and a ruby of “forty-six grains” estimated at 36,000 pounds.

They would essentially serve as a guarantee for the payment of the former Governor General’s debts, including the 175,000 guilders he had pledged to the Bank of Holland. The man had spent part of his personal fortune to make the Company successful and, despite the legal proceedings, he would never recover the estimated 13 million pound cost of his businesses. After the death of his wife and daughter, it was as a bitter man that he wrote in a memoir a few days before his death: “I sacrificed my youth, my fortune, my life, to enrich my nation in Asia”.Sources : Des minutes qui font l’histoire, Somogy Editions d’Art / Archives nationales, Chambre des notaires de Paris, 2012 / 122 Minutes d’histoire, Acte des notaires de Paris, XVIème-XXème siècles, Somogy Editions d’Art / Archives nationales, Chambre des notaires de Paris, 2012

1849 - Inventory after death of Frédéric Chopin

Paper, handwritten, 10 ff, 32.5 x 23 cm, Paris, National Archives, Central Register, ET/VIII/1639 (RS/639)

23 November 1849The Franco-Polish composer and virtuoso pianist Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) died in Paris on 17 October 1849. His inventory after death was only carried out on 23 November, in the apartment overlooking the courtyard that he rented at 12, place Vendôme. It was indeed necessary, for the inventory, to wait for the arrival in Paris of his sister Louise and the powers of attorney of their mother Justyna and their younger sister Isabelle, who were living in Warsaw.

From 14 October, Chopin, who had always been in poor health and feared winters, was bedridden, subject to attacks of exhausting coughs. His friends gather around him. A piano was brought into the dying man’s room, and Countess Delphine Potocka, Chopin’s first muse, pupil and protector in Paris, who arrived from Nice, began to sing. The next day, increasingly weakened, he asked that his body be opened once dead so as not to risk being buried alive, and demanded that his unfinished compositions be burned.

The inventory describes the interior in which Chopin lived his last hours, living room and bedroom: several mahogany pieces of furniture – but no piano -, a few trinkets, a fairly well chosen wardrobe – waistcoats and a morning jacket, two satin and silk sultans, silk ties, etc. – which are a reminder of the care Chopin took of his appearance. Nothing, however, very expensive, all the furniture, silverware and jewellery amounting to 3,585 francs.

Source: Des minutes qui font l’histoire, Somogy Editions d’Art / Archives nationales, Chambre des notaires de Paris, 2012

1850 - Mutual gift between spouses by Honoré de Balzac and Constance Victoire Rzeweska

Paper, handwritten, 30 x 22.5 cm (two acts), Paris, National Archives, Central Register, ET/CXVI/778 (RS/568)

4 June 1850On 14 March 1850, Honoré de Balzac, the author of the Comédie Humaine, married Countess Evelyne Hanska in Ukraine.

The couple had only been back in Paris for a few days when, on 4 June 1850, before their notary, they made a gift to each other.

Balzac died in the summer months, on 18 August 1850.

It was in 1833 that the already famous novelist met Constance Victoire Rzewuska (Evelyne Hanska née Ewelina Rzewuska) with whom he fell passionately in love following an epistolary exchange. Evelyne was of Polish origin; she was married and had a young daughter. In 1834, they became lovers. Despite the husband’s death in 1842, Balzac did not marry her until 1850, on 14 March, in Berditcheff near Kiev (Ukraine). Balzac’s letters to his mistress were published under the title Lettres à l’étrangère, “Letters to a Foreigner”, in 1906.Source: Des minutes qui font l’histoire, Somogy Editions d’Art / Archives nationales, Chambre des notaires de Paris, 2012

1861 - Inventory after death of the Dowager Queen of Sweden and Norway, in her hotel, rue d'Anjou

Paper, handwritten, 31 ff, 30,5 x 22 cm, Paris, Archives Nationales, Central Register, ET/LV/456 (RS/298)

19 February 1861The dowager queen of Sweden and Norway who died in Stockholm on 17 December 1860 at the age of 83 was none other than Désirée Clary. Originally from Marseille, she was the daughter of an alderman from the city. We know that, in her youth, she was engaged for a few months to Napoleon Bonaparte before she met Josephine de Beauharnais. Désirée Clary married another general, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, in August 1789. In August 1810, with the old King of Sweden Charles XIII not having any descendants, Bernadotte was elected Crown Prince of Sweden. His wife left for Scandinavia before returning to Paris in 1811 to live in her hotel on rue d’Anjou.

Upon the death of King Charles XIII in February 1818, Bernadotte ascended the throne under the name of Charles XIV, but failed to convince Désirée to follow him. She did not return to Stockholm until 1822 for the marriage of their son and to be crowned Queen of Sweden and Norway. When her husband died on 8 March 1844, when their son Oscar ascended the throne, Désirée thought of returning to France, but she ended up staying in Sweden until her death, and did not see her hotel on rue d’Anjou again.

In 1861, the five-day inventory of the hotel was carried out on behalf of King Charles XV, son of Oscar I, and his brothers and sister. A previous inventory of the hotel had been drawn up in October 1844, after the death of Charles XIV.

Source: 122 Minutes d’histoire, Acte des notaires de Paris, XVIème-XXème siècles, Somogy Editions d’Art / Archives nationales, Chambre des notaires de Paris, 2012

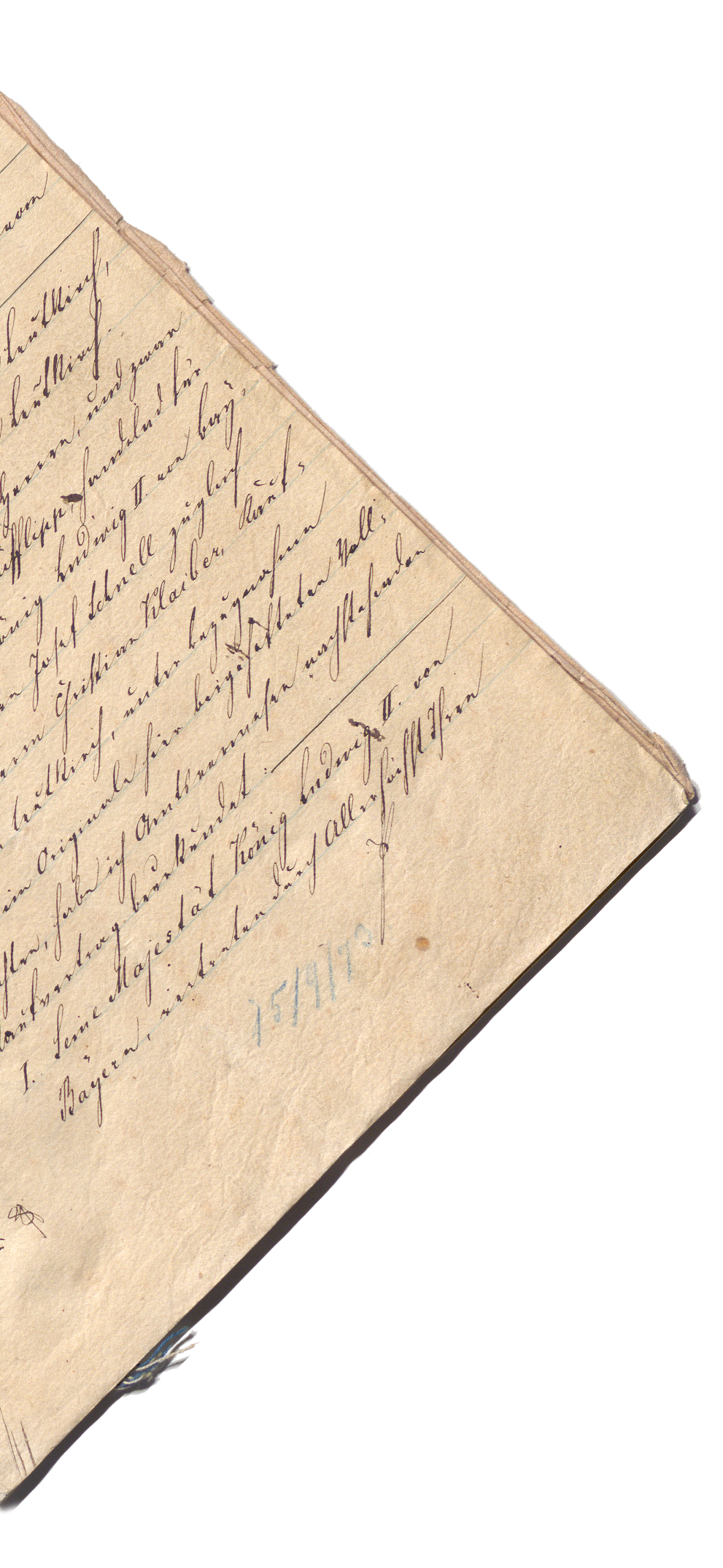

1881 - Holographic codicil in Victor Hugo’s will

“I will close the earthly eye; but the spiritual eye will remain open wider than ever.” These words, which conclude this addition to the holographic will of 5 May 1864, characterise the brilliance of Hugolian thought and define in a few characters the content of several acts. The holographic will of 5 May 1864, written in Guernsey, is quite brief and approves the equal division of his property between his two children allowed by “French law, one of the excellent results of our great revolution”. Quite quickly, the tragedies of life, such as the loss of his two sons, led him to add a sealed will, that is, one that was sealed until death and deposited with the notary in the presence of witnesses, and several holographic codicils written in 1875.

Through them, it is not only the writer, but above all the man and his vision of the world that shines through. First, the writer, because particular care is taken to safeguard the future of his writings, which he classifies into three categories – works that have been completed, works begun in part but not yet completed, and drafts and fragments – and for which he develops a publication programme to protect them as best he can, just as a “courageous woman who, during the coup d’état, saved [his] life at the risk of her own and who then saved the trunk containing [his] manuscripts” had protected them. Because man is also present in this codicil, and in particular the father who gives his sick daughter and two grandchildren his blessing. Then the politician, whose choice of executors, Jules Grévy, Léon Say and Léon Gambetta, speaks volumes about his opinions and struggles. Finally, the humanist, who gives 40,000 francs to the needy and wants “to be carried to the cemetery in the hearse of the poor”, does not make us forget the visionary. While he predicted that the National Library would “one day become the Library of the United States of Europe”, Hugo also knew that his work would remain immortal, like the spiritual eye mentioned above. Faced with death, Hugo summed up his religious convictions in a powerful way. “God. The soul. Responsibility. This triple notion is enough for man. It was enough for me. It is the true religion.”. These words reveal a deep and personal faith in which God is “Truth, light, justice, conscience”, but in which his anticlericalism is nevertheless present; thus he rejects “the prayer of all the churches”, but asks for “a prayer to all souls”. All the complexity of the great man is there, and undoubtedly all his genius.

Source: 122 Minutes d’histoire, Acte des notaires de Paris, XVIe-XXe siècles, Somogy Editions d’Art / Archives nationales, Chambre des notaires de Paris, 2012.